Wilde, Oscar

This article is about the 19th-century author. For other uses, see Oscar Wilde (disambiguation).

| Oscar Wilde |

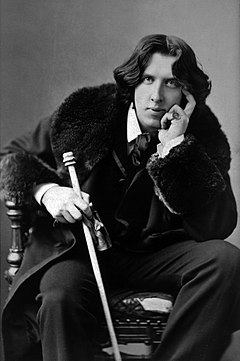

Photograph taken in 1882 by Napoleon Sarony |

| Born |

16 October 1854(1854-10-16)

Dublin, Ireland |

| Died |

30 November 1900(1900-11-30) (aged 46)

Paris, France |

| Occupation |

Writer |

| Language |

English, French |

| Nationality |

Irish |

| Alma mater |

Trinity College, Dublin |

| Period |

Victorian era |

| Genres |

Drama, short story, dialogue, journalism |

| Literary movement |

Aestheticism |

| Notable work(s) |

The Importance of Being Earnest, The Picture of Dorian Gray |

| Spouse(s) |

Constance Lloyd (1884-1898) |

| Children |

Cyril Holland, Vyvyan Holland |

| Relative(s) |

Sir William Wilde, Lady Jane Francesca Wilde |

Influences

Plato, Aristotle, Greek literature, William Shakespeare, Théophile Gautier, French literature, Joris-Karl Huysmans, John Keats, Victor Hugo, Walter Pater, John Ruskin, James McNeill Whistler, John Pentland Mahaffy

|

Influenced

Jorge Luis Borges, James Joyce, Samuel Beckett, Paul Merton, James Morrow, Enchi Fumiko, Erico Verissimo, Irène Némirovsky, André Gide, Max Beerbohm, Stephen Fry, Lawrence Durrell, Camille Paglia, Dave Sim, Mateiu Caragiale, Saki, Amanda Filipacchi, W. H. Pugmire, Ronald Firbank, Christopher Hitchens, Morrissey, Peter Doherty, Benjamin Tucker [1], Renzo Novatore

|

|

| Signature |

|

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 1854 – 30 November 1900) was an Irish writer, poet, and prominent aesthete who, after writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, became one of London's most popular playwrights in the early 1890s. Today he is remembered for his epigrams, plays and the tragedy of his imprisonment, followed by his early death.

Wilde's parents were successful Dublin intellectuals and from an early age he was tutored at home, where he showed his intelligence, becoming fluent in French and German. He attended boarding school for six years, then matriculated to university at seventeen years of age. Reading Greats, Wilde proved himself to be an outstanding classicist, first at Dublin, then at Oxford. His intellectual horizons were broad: he was deeply interested in the rising philosophy of aestheticism (led by two of his tutors, Walter Pater and John Ruskin) though he also profoundly explored Roman Catholicism and finally converted on his deathbed.

After university Wilde moved to London, into fashionable cultural and social circles. As a spokesman for aestheticism, he tried his hand at various literary activities; he published a book of poems, lectured America and Canada on the new "English Renaissance in Art" and then returned to London to work prolifically as a journalist for four years. Known for his biting wit, flamboyant dress, and glittering conversation, Wilde was one of the best known personalities of his day. At the turn of the 1890s, he refined his ideas about the supremacy of art in a series of dialogues and essays; though it was his only novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray, which began a more lasting oeuvre. The opportunity to construct aesthetic details precisely, combined with larger social themes, drew Wilde to writing drama. He wrote Salome in French in Paris in 1891, but it was refused a licence. Unperturbed, Wilde produced four society comedies in the early 1890s, which made him one of the most successful playwrights of late Victorian London.

At the height of his fame and success, whilst his masterpiece, The Importance of Being Earnest, was still on stage in London, Wilde sued his lover's father for libel. After a series of trials, Wilde was convicted of gross indecency with other men and imprisoned for two years, held to hard labour. In prison he wrote De Profundis, a long letter which discusses his spiritual journey through his trials, forming a dark counterpoint to his earlier philosophy of pleasure. Upon his release he left immediately for France, never to return to Ireland or Britain. There he wrote his last work, The Ballad of Reading Gaol, a long poem commemorating the harsh rhythms of prison life. He died destitute in Paris at the age of forty-six.

[edit] Early life

Statue of Oscar Wilde by Danny Osborne in Dublin's Merrion Square (Archbishop Ryan Park)

Oscar Wilde was born at 21 Westland Row, Dublin (now home of the Oscar Wilde Centre, Trinity College, Dublin) the second of three children born to Sir William Wilde and Jane Francesca Wilde, two years behind William ("Willie"). Jane Wilde, under the pseudonym "Speranza" (the Italian word for 'Hope'), wrote poetry for the revolutionary Young Irelanders in 1848 and was a life-long Irish nationalist.[2] She read the Young Irelanders' poetry to Oscar and Willie, inculcating a love of these poets in her sons.[3] Lady Wilde's interest in the neo-classical revival showed in the paintings and busts of ancient Greece and Rome in her home.[3] William Wilde was Ireland's leading oto-ophthalmologic (ear and eye) surgeon and was knighted in 1864 for his services as medical adviser and assistant commissioner to the censuses of Ireland.[4] He also wrote books about Irish archaeology and peasant folklore. A renowned philanthropist, his dispensary for the care of the city's poor at the rear of Trinity College, Dublin, was the forerunner of the Dublin Eye and Ear Hospital, now located at Adelaide Road.[4]

In addition to his children with his wife, Sir William Wilde was the father of three children born out of wedlock before his marriage: Henry Wilson, born in 1838, and Emily and Mary Wilde, born in 1847 and 1849, respectively, of different parentage to Henry. Sir William acknowledged paternity of his illegitimate children and provided for their education, but they were reared by his relatives rather than with his wife and legitimate children.[5]

In 1855, the family moved to No. 1 Merrion Square, where Wilde's sister, Isola, was born the following year. The Wildes' new home was larger and, with both his parents' sociality and success soon became a "unique medical and cultural milieu"; guests at their salon included Sheridan le Fanu, Charles Lever, George Petrie, Isaac Butt, William Rowan Hamilton and Samuel Ferguson.[3]

Until he was nine, Oscar Wilde was educated at home, where a French bonne and a German governess taught him their languages. He then attended Portora Royal School in Enniskillen, County Fermanagh.[6] Until his early twenties, Wilde summered at the villa his father built in Moytura, County Mayo.[7] There the young Wilde and his brother Willie played with George Moore.

Isola died aged eight of meningitis. Wilde's poem Requiescat is dedicated to her memory:[8]

"Tread lightly, she is near

Under the snow

Speak gently, she can hear

the daisies grow"

[edit] University education

[edit] Trinity College, Dublin

Wilde left Portora with a royal scholarship to read classics at Trinity College, Dublin, from 1871 to 1874,[9] sharing rooms with his older brother Willie Wilde. Trinity, one of the leading classical schools, set him with scholars such as R.Y. Tyrell, Arthur Palmer, Edward Dowden and his tutor, J.P. Mahaffy who inspired his interest in Greek literature. As a student Wilde worked with Mahaffy on the latter's book Social Life in Greece.[10] Wilde, despite later reservations, called Mahaffy "my first and best teacher" and "the scholar who showed me how to love Greek things".[11] For his part Mahaffy boasted of having created Wilde; later, he would name him "the only blot on my tutorship".[12]

The University Philosophical Society also provided an education, discussing intellectual and artistic subjects such as Rosetti and Swinburne weekly. Wilde quickly became an established member – the members' suggestion book for 1874 contains two pages of banter (sportingly) mocking Wilde's emergent aestheticism. He presented a paper entitled "Aesthetic Morality".[13] At Trinity, Wilde established himself as an outstanding student: he came first in his class in his first year, won a scholarship by competitive examination in his second, and then, in his finals, won the Berkeley Gold Medal, the University's highest academic award in Greek.[14] He was encouraged to compete for a demyship to Magdalen College, Oxford – which he won easily, having already studied Greek for over nine years.

[edit] Magdalen College, Oxford

At Magdalen he read Greats from 1874 to 1878, and from there he applied to join the Oxford Union, but failed to be elected.[15]

Attracted by its dress, secrecy, and ritual, Wilde petitioned the Apollo Masonic Lodge at Oxford, and was soon raised to the "Sublime Degree of Master Mason".[16] During a resurgent interest in Freemasonry in his third year, he commented he "would be awfully sorry to give it up if I secede from the Protestant Heresy".[17] He was deeply considering converting to Catholicism, discussing the possibility with clergy several times. In 1877, Wilde was left speechless after an audience with Pope Pius IX in Rome.[18] He eagerly read Cardinal Newman's books, and became more serious in 1878, when he met the Reverend Sebastian Bowden, a priest in the Brompton Oratory who had received some high profile converts. Neither his father, who threatened to cut off his funds, nor Mahaffy thought much of the plan; but mostly Wilde, the supreme individualist, balked at the last minute from pledging himself to any formal creed. On the appointed day of his baptism, Father Bowden received a bunch of altar lilies instead. Wilde retained a lifelong interest in Catholic theology and liturgy.[19]

While at Magdalen College, Wilde became particularly well known for his role in the aesthetic and decadent movements. He wore his hair long, openly scorned "manly" sports though he occasionally boxed,[16] and decorated his rooms with peacock feathers, lilies, sunflowers, blue china and other objets d'art, once remarking to friends whom he entertained lavishly, "I find it harder and harder every day to live up to my blue china."[20] The line quickly became famous, accepted as a slogan by aesthetes but used against them by critics who sensed in it a terrible vacuousness.[20] Some elements disdained the aesthetes, but their languishing attitudes and showy costumes became a recognised pose.[21] Wilde was once physically attacked by a group of four fellow students, and dealt with them single-handedly, surprising critics.[22] By his third year Wilde had truly begun to create himself and his myth, and saw his learning developing in much larger ways than merely the prescribed texts. This attitude resulted in him being rusticated for one term, when he nonchalantly returned to college late from a trip to Greece with Prof. Mahaffy.[23]

Wilde did not meet Professor Walter Pater until his third year, but had been enthralled by his Studies in the History of the Renaissance, published during Wilde's final year in Trinity.[24] Pater argued that man's sensibility to beauty should be refined above all else, and that each moment should be felt to its fullest extent. Years later in De Profundis, Wilde called Pater's Studies... "that book that has had such a strange influence over my life".[25] He learned tracts of the book by heart, and carried it with him on travels in later years. Pater gave Wilde his sense of almost flippant devotion to art, though it was Professor John Ruskin who gave him a purpose for it.[26] Ruskin despaired at the self-validating aestheticism of Pater; for him the importance of art lay in its potential for the betterment of society. He too admired beauty, but it must be allied with and applied to moral good. When Wilde eagerly attended his lecture series The Aesthetic and Mathematic Schools of Art in Florence, he learned about aesthetics as simply the non-mathematical elements of painting. Despite being given to neither early rising nor manual labour, Wilde volunteered for Ruskin's project to convert a swampy country lane into a smart road neatly edged with flowers.[26]

Wilde won the 1878 Newdigate Prize for his poem Ravenna, which reflected on his visit there the year before, and he duly read it at Encaenia.[27] In November 1878, he graduated with a rare double first in his B.A. of Classical Moderations and Literae Humaniores (Greats). Wilde wrote a friend, "The dons are 'astonied' beyond words – the Bad Boy doing so well in the end!"[28]

[edit] Apprenticeship of an aesthete: 1880s

1881 caricature in

Punch, the caption reads: "O.W.", "Oh, I eel just as happy as a bright sunflower,

Lays of Christy Ministrely, "Aesthete of Aesthetes!/What's in a name!/The Poet is Wilde/But his poetry's tame"

[edit] Debut in society

After graduation from Oxford, Wilde returned to Dublin, where he met again Florence Balcombe, a childhood sweetheart. She, however, became engaged to Bram Stoker (who later wrote Dracula), and they married in 1878.[29] Wilde was disappointed but stoic: he wrote to her, remembering "the two sweet years – the sweetest years of all my youth" they had spent together.[30] He also stated his intention to "return to England, probably for good". This he did in 1878, only briefly visiting Ireland twice.[31]

Unsure of his next step, he wrote to various acquaintances enquiring about Classics positions at Oxbridge.[32] The Rise of Historical Criticism was his submission for the Chancellor's Essay prize of 1879, which, though no longer a student, he was still eligible to enter. Its subject, "Historical Criticism among the Ancients" seemed ready-made for Wilde – with both his skill in composition and ancient learning – but he struggled to find his voice with the long, flat, scholarly style.[33] Unusually, no prize was awarded that year.[33][Notes 1] With the last of his inheritance from the sale of his father's houses, he set himself up as a bachelor in London.[34] The 1881 British Census listed Wilde as a boarder at 1 Tite Street, Chelsea, where Frank Miles, a society painter, was the head of the household.[35] Wilde would spend the next six years in London and Paris, and in the United States where he travelled to deliver lectures.

He had been publishing lyrics and poems in magazines since his entering Trinity College, especially in Kottabos and the Dublin University Magazine. In mid-1881, at 27 years old, Poems collected, revised and expanded his poetic efforts.[36] The book was generally well received, and sold out its first print run of 750 copies, prompting further printings in 1882. Bound in a rich, enamel, parchment cover (embossed with gilt blossom) and printed on hand-made Dutch paper, Wilde would present many copies to the dignitaries and writers who received him over the next few years.[37] The Oxford Union condemned the book for alleged plagiarism in a tight vote. The librarian, who had requested the book for the library, returned the presentation copy to Wilde with a note of apology.[38][39] Richard Ellmann argues that Wilde's poem Hélas was a sincere, though flamboyant, attempt to explain the dichotomies he saw in himself:[40]

To drift with every passion till my soul

Is a stringed lute on which all winds can play

[edit] America: 1882

Keller cartoon from the

Wasp of San Francisco depicting Wilde on the occasion of his visit there in 1882

Aestheticism was sufficiently in vogue to be caricatured by Gilbert and Sullivan in Patience (1881). Richard D'Oyly Carte, an English Impressario, invited Wilde on a lecture tour of North America, simultaneously priming the pump for the U.S. tour of Patience and selling the most charming English aesthete to the American public. Wilde arrived on 3 January 1882 aboard the SS Arizona and criss-crossed the country on a gruelling schedule, lecturing in a new town every few days.[Notes 2] Originally planned to last four months, it was continued for over a year due to the commercial success. Wilde sought to juxtapose the beauty he saw in art onto daily life.[41] This was a practical as well as philosophical project: in Oxford he had surrounded himself with blue china and lilies, now one of his lectures was on interior design. When as to explain reports that he had paraded down Piccadilly in London carrying a lily, long hair flowing, Wilde replied, "It's not whether I did it or not that's important, but whether people believed I did it".[41] Wilde believed that the artist should hold forth higher ideals, and that pleasure and beauty would replace utilitarian ethics.[42]

Wilde and aestheticism were both mercilessly caricatured and criticised in the press, Springfield Republican, for instance, commented on Wilde's behaviour during his visit to Boston to lecture on aestheticism, suggesting that Wilde's conduct was more of a bid for notoriety rather than a devotion to beauty and the aesthetic. T.W. Higginson, a cleric and abolitionist, wrote in "Unmanly Manhood" of his general concern that Wilde, "whose only distinction is that he has written a thin volume of very mediocre verse", would improperly influence the behaviour of men and women.[43] Though his press reception was hostile, Wilde was well received in diverse settings across America; he drank whiskey with miners in Leadville, Colorado and was fêted at the most fashionable salons in every city he visited.[44]

[edit] London life and marriage

His earnings, plus expected income from The Duchess of Padua, allowed him to move to Paris between February and mid-May 1883; there he met Robert Sherard, whom he entertained constantly. "We are dining on the Duchess tonight", Wilde would declare before taking him to a fancy restaurant.[45] In August he briefly returned to New York for the production of Vera, his first play, after it was turned down in London. He reportedly entertained the other passengers with Ave Imperatrix!, A Poem On England, about the rise and fall of empires. E.C. Stedman, in Victorian Poets describes this "lyric to England" as "manly verse – a poetic and eloquent invocation".[46][Notes 3] Wilde's presence was again notable, the play was initially well received by the audience, but when the critics returned lukewarm reviews attendance fell sharply and the play closed a week after it had opened.[47]

Robert Ross at twenty-four

He was left to return to England and lecturing: Personal Impressions of America, The Value of Art in Modern Life, and Dress were among his topics.

In London, he had been introduced to Constance Lloyd in 1881, daughter of Horace Lloyd, a wealthy Queen's Counsel. She happened to be visiting Dublin in 1884, when Wilde was lecturing at the Gaiety Theatre (W. B. Yeats, then aged eighteen, was also among the audience). He proposed to her, and they married on the 29 May 1884 at the Anglican St. James Church in Paddington in London.[48] Constance's annual allowance of £250 was generous for a young woman (it would be equivalent to about £19,300 in current value), but the Wildes' tastes were relatively luxurious and, after preaching to others for so long, their home was expected to set new standards of design.[49] No. 16, Tite Street was duly renovated in seven months at considerable expense. The couple had two sons, Cyril (1885) and Vyvyan (1886). Wilde was the sole literary signatory of George Bernard Shaw's petition for a pardon of the anarchists arrested (and later executed) after the Haymarket massacre in Chicago in 1886.[50]

Robert Ross had read Wilde's poems before they met, and he was unrestrained by the Victorian prohibition against homosexuality, even to the extent of estranging himself from his family. A precocious seventeen year old, by Richard Ellmann's account, he was "...so young and yet so knowing, was determined to seduce Wilde".[51] Wilde, who had long alluded to Greek love, and – though an adoring father – was put off by the carnality of his wife's second pregnancy, succumbed to Ross in Oxford in 1886.[52]

[edit] Prose writing: 1886-91

[edit] Journalism and editorship: 1886–89

Oscar Wilde reclines with

Poems for Napoleon Sarony in New York in 1882. Wilde often liked to appear idle, though in fact he worked hard; by the late ’80s he was a father, an editor, and a writer.

[53]

Criticism over artistic matters in the Pall Mall Gazette provoked a letter in self-defence, and soon Wilde was a contributor to that and other journals during the years 1885–87. He enjoyed reviewing and journalism, it was a form that suited his style: he could organise and share his views on art, literature and life, yet it was less tedious than lecturing. Buoyed up, his reviews were largely chatty and positive.[54] Wilde, like his parents before him, also supported the cause of Irish Nationalism. When Charles Stewart Parnell was falsely accused of inciting murder Wilde wrote a series of astute columns defending him in the Daily Chronicle.[50]

His flair, having previously only been put into socialising, suited journalism and did not go unnoticed. With his youth nearly over, and a family to support, in mid-1887 Wilde became the editor of The Lady's World magazine, his name prominently appearing on the cover.[55] He promptly renamed it The Woman's World and raised its tone, adding serious articles on parenting, culture, and politics, keeping discussions of fashion and arts. Two pieces of fiction were usually included, one to be read to children, the other for the ladies themselves. Wilde used his wide artistic acquaintance to solicit good contributions, including those of Lady Wilde and his wife Constance, while his own "Literary and Other Notes" were themselves popular and amusing.[56] In Victorian society, Wilde was a colourful agent provocateur: his art, like his paradoxes, sought to subvert as well as sparkle. His own estimation of himself was of one who "stood in symbolic relations to the art and culture of my age".[57] The initial vigour and excitement he brought to the job began to fade as administration, commuting and office life became tedious. His lack of interest showed in the magazine's declining quality and flagging sales. Increasingly sending instructions by letter, he began a new period of creative work and his own column appeared less regularly.[58][59] In October 1889, Wilde had finally found his voice in prose and, at the end of the second volume, Wilde left The Woman's World.[60] The magazine outlasted him by one volume.[58]

[edit] Stories

Main articles: Lord Arthur Savile's Crime and Other Stories and The House of Pomegranates

Wilde published The Happy Prince and Other Tales in 1888, and had been regularly writing fairy stories for magazines. In 1891 published two more collections, Lord Arthur Savile's Crime and Other Stories, and in September The House of Pomegranates was dedicated "To Constance Mary Wilde".[61] The Portrait of Mr. W.H., which Wilde had begun in 1887, was first published in Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine in July 1889.[62] It is a short story, which reports a conversation, in which the theory that Shakespeare's sonnets were written out of the poet's love of the boy actor "Willie Hughes", is advanced, retracted, and then propounded again. The only evidence for this is two supposed puns within the sonnets themselves.[63] The anonymous narrator is at first sceptical, then believing, finally flirtatious with the reader: he concludes that "there is really a great deal to be said of the Willie Hughes theory of Shakespeare's sonnets.[64] By the end fact and fiction have melded together.[65] "You must believe in Willie Hughes" Wilde told an acquaintance, "I almost do, myself".[65]

[edit] Essays and dialogues

Main articles: The Soul of Man under Socialism and The Decay of Lying

Wilde, having tired of journalism, had been busy setting out his aesthetic ideas more fully in a series of longer prose pieces which were published in the major literary-intellectual journals of the day. The Decay of Lying:A Dialogue was in Eclectic Magazine in February 1889[66] and Pen, Pencil and Poison, a satirical biography of Thomas Wainewright, was published later in the year by his friend Frank Harris, editor of the Fortnightly Review.[67] Two of Wilde's four writings on aesthetics were dialogues, though Wilde was earning his living as a writer rather than a lecturer, he remained with an oral tradition of sorts. Wilde had always excelled as a wit and raconteur, and when writing often arranged phrases he had created until they formed a cohesive work.[68]

With the abolition of private property, then, we shall have true, beautiful, healthy Individualism. Nobody will waste his life in accumulating things, and the symbols for things. One will live. To live is the rarest thing in the world. Most people exist, that is all.

The Soul of Man under Socialism, 1891

Wilde was concerned about the effect of moralising on art since he believed in the redemptive, developmental power of art, "Art is individualism, and individualism is a disturbing and disintegrating force. There lies its immense value. For what it seeks is to disturb monotony of type, slavery of custom, tyranny of habit, and the reduction of man to the level of a machine."[69] He felt political conditions should establish this primacy, concluding that the government most amenable to artists was no government at all. Wilde envisions a society where mechanisation has freed human effort from the burden of necessity, effort which can instead be expended on artistic creation. George Orwell summarised it thus, "In effect, the world will be populated by artists, each striving after perfection in the way that seems best to him."[70] This point of view did not align him with the Fabians, the leading intellectual socialists of the time who advocated using state apparatus to change social conditions.[71]

Wilde considered including The Soul of Man (later published separately in 1895) and The Portrait of Mr. W.H. in his essay-anthology published in 1891, but decided to limit it to essays on aesthetics, which were thoroughly revised and packaged as Intentions.[72] 1891 turned out to be Wilde's annus mirabilis, apart from his story collections he also produced his only novel.

[edit] The Picture of Dorian Gray

Main article: The Picture of Dorian Gray

The first version of The Picture of Dorian Gray was published as the lead story in the July 1890 edition of Lippincott's Monthly Magazine, along with five others.[73] The story begins as Gray's portrait is being completed, and he talks with the libertine Lord Henry Wotton, who has a curious influence on him. When Gray, who has a "face like ivory and rose leaves" sees his finished portrait he breaks down, distraught that his beauty will fade, but the portrait stay beautiful, inadvertently making a faustian bargain. For Wilde, the purpose of art would guide life if beauty alone were its object. Thus Gray's portrait allows him to escape the corporeal ravages of his hedonism, (and Miss Prism mistakes a baby for a book in The Importance of Being Earnest), Wilde sought to juxtapose the beauty he saw in art onto daily life.[41]

Reviewers immediately criticised the novel's content and decadence, and Wilde vigorously responded in print.[74] Writing to the Editor of the Scots Observer, he clarified his stance on ethics and aesthetics in art "If a work of art is rich and vital and complete, those who have artistic instincts will see its beauty and those to whom ethics appeal more strongly will see its moral lesson."[75] He nevertheless revised it extensively for book publication in 1891: six new chapters were added, some overt decadence passages and homo-eroticism excised, and a preface consisting of twenty two epigrams, such as "Books are well written, or badly written. That is all. " was included.[76][77] Contemporary reviewers and modern critics have postulated numerous po