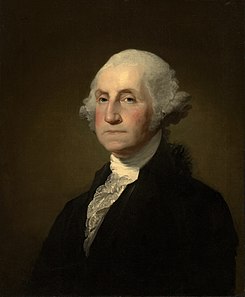

Washington, George

This article is about the first President of the United States. For other uses, see George Washington (disambiguation).

| George Washington |

|

1st President of the United States

|

In office

April 30, 1789 – March 4, 1797 |

| Vice President |

John Adams |

| Preceded by |

Office Created |

| Succeeded by |

John Adams |

1st Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army

|

In office

June 15, 1775 – December 23, 1783 |

| Appointed by |

Continental Congress |

| Succeeded by |

Henry Knox |

In office

July 13, 1798 – December 14, 1799 |

| President |

John Adams |

| Preceded by |

James Wilkinson |

| Succeeded by |

Alexander Hamilton |

|

| Born |

February 22, 1732(1732-02-22)

Westmoreland County, Colony of Virginia |

| Died |

December 14, 1799(1799-12-14) (aged 67)

Mount Vernon, Virginia |

| Resting place |

Washington family vault,

Mount Vernon |

| Nationality |

American

British subject (prior to 1776) |

| Political party |

None |

| Spouse(s) |

Martha Dandridge Custis Washington |

| Children |

none |

| Occupation |

Farmer (planter)

soldier (officer) |

| Religion |

Church of England / Episcopal |

| Signature |

|

| Military service |

| Allegiance |

Kingdom of Great Britain Kingdom of Great Britain

United States of America United States of America |

| Service/branch |

Virginia provincial militia

Continental Army

United States Army |

| Years of service |

militia: 1752–1758

Continental Army: 1775–1783

U. S. Army: 1798–1799 |

| Rank |

Lieutenant General Lieutenant General

General of the Armies of the United States (posthumously in 1976) General of the Armies of the United States (posthumously in 1976) |

| Commands |

Colony of Virginia's provincial regiment

Continental Army

United States Army |

| Battles/wars |

French and Indian War

- Battle of Jumonville Glen

- Battle of Fort Necessity

- Battle of the Monongahela

- Battle of Fort Duquesne

American Revolutionary War

- Boston campaign

- New York campaign

- New Jersey campaign

- Philadelphia campaign

- Yorktown Campaign

|

| Awards |

Congressional Gold Medal, Thanks of Congress |

George Washington (February 22, 1732 – December 14, 1799) was the dominant military and political leader of the new United States of America from 1775 to 1797, leading the American victory over Britain in the American Revolutionary War as commander in chief of the Continental Army, 1775–1783, and presiding over the writing of the Constitution in 1787. As the unanimous choice to serve as the first President of the United States (1789–1797), he developed the forms and rituals of government that have been used ever since, such as using a cabinet system and delivering an inaugural address. The president built a strong, well-financed national government that avoided war, suppressed rebellion and won acceptance among Americans of all types. Acclaimed ever since as the "Father of his country", Washington, along with Abraham Lincoln, has become a central icon of republican values, self sacrifice in the name of the nation, American nationalism and the ideal union of civic and military leadership.

In Colonial Virginia Washington was born into the provincial gentry in a wealthy, well connected family that owned tobacco plantations using slave labor. Washington was home schooled by his father and older brother but both died young and Washington became attached to the powerful Fairfax clan. They promoted his career as surveyor and soldier. Strong, brave, eager for combat and a natural leader, young Washington quickly became a senior officer of the colonial forces, 1754–58, during the first stages of the French and Indian War. Indeed his rash actions helped precipitate the war.

Washington's experience, his military bearing, his leadership of the Patriot cause in Virginia, and his political base in the largest colony made him the obvious choice of the Second Continental Congress in 1775 as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army to fight the British in the American Revolution. He forced the British out of Boston in 1776, but was defeated and nearly captured later that year when he lost New York City. After crossing the Delaware River in the dead of winter he defeated the British in two battles and retook New Jersey. Because of his strategy, Revolutionary forces captured two major British armies at Saratoga in 1777 and Yorktown in 1781. Negotiating with Congress, governors, and French allies, he held together a tenuous army and a fragile nation amid the threats of disintegration and invasion. Historians give the commander in chief high marks for his selection and supervision of his generals, his encouragement of morale, his coordination with the state governors and state militia units, his relations with Congress, and his attention to supplies, logistics, and training. In battle, however, Washington was repeatedly outmaneuvered by British generals with larger armies. In the New York campaign of 1776 and the Philadelphia campaign, General William Howe repeatedly flanked him, and eventually took both cities, although the British abandoned Philadelphia after France entered the war in 1778, and Washington forced a major inconclusive battle at Monmouth Court House during their march to New York. Washington is given full credit for the strategies that forced the British evacuation of Boston in 1776 and the surrender at Yorktown in 1781. After victory was finalized in 1783, Washington resigned rather than seize power, and returned to his plantation at Mount Vernon; this prompted his erstwhile enemy King George III to call him "the greatest character of the age".[1][2]

Washington presided over the Constitutional Convention that drafted the United States Constitution in 1787 because of his dissatisfaction with the weaknesses of Articles of Confederation that had time and again impeded the war effort. Washington became President of the United States in 1789. Once President, he attempted to bring rival factions together in order to create a more unified nation. He supported Alexander Hamilton's programs to pay off all the state and national debts, implement an effective tax system, and create a national bank, despite opposition from Thomas Jefferson. Washington proclaimed the U.S. neutral in the wars raging in Europe after 1793. He avoided war with Britain and guaranteed a decade of peace and profitable trade by securing the Jay Treaty in 1795, despite intense opposition from the Jeffersonians. Although never officially joining the Federalist Party, he supported its programs. Washington's farewell address was a primer on republican virtue and a stern warning against partisanship, sectionalism, and involvement in foreign wars. Washington had a vision of a great and powerful nation that would be built on republican lines using federal power. He sought to use the national government to improve the infrastructure, open the western lands, create a national university, promote commerce, found a capital city (later named Washington, D.C.), reduce regional tensions and promote a spirit of nationalism. "The name of AMERICAN," he said, must override any local attachments."[3] At his death Washington was hailed as "first in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen".[4] The Federalists made him the symbol of their party, but for many years the Jeffersonians continued to distrust him and delayed building the Washington Monument. As the leader of the first successful revolution against a colonial empire in world history, Washington became an international icon for liberation and nationalism. His symbolism especially resonated in France and Latin America.[5] Historical scholars consistently rank him as one of the two or three greatest presidents.

Early life (1732–1753)

Forensic reconstruction of Washington at 19, based on analysis of his clothing and a life mask

George Washington, the first child of Augustine Washington (1694–1743) and his second wife, Mary Ball Washington (1708–1789), was born on their Pope's Creek Estate near present-day Colonial Beach in Westmoreland County, Virginia. According to the Julian calendar (which was in effect at the time), Washington was born on February 11, 1731 (O.S.); according to the Gregorian calendar, which was adopted in Britain and its colonies in 1752, he was born on February 22, 1732.[6][7][Note 1] Washington's ancestors were from Sulgrave, England; his great-grandfather, John Washington, immigrated to Virginia in 1657.[8] George's father Augustine was a slave-owning tobacco planter who later tried his hand in iron-mining ventures.[9] His mother Mary lived to see her son become famous, though she had a strained relationship with him. In George's youth, the Washingtons were moderately prosperous members of the Virginia gentry, of "middling rank" rather than one of the leading families.[10]

Washington was the first-born child from his father's marriage to Mary Ball Washington. Six of his siblings reached maturity including two older half-brothers, Lawrence and Augustine, from his father's first marriage to Jane Butler Washington and four full-siblings, Samuel, Elizabeth(Betty), John Augustine and Charles. Three siblings died before becoming adults: his full-sister Mildred died when she was about one, and two half-siblings Butler and Jane died in their teens. George's father died when George was 11 years old, after which George's half-brother Lawrence became a surrogate father and role model. William Fairfax, Lawrence's father-in-law and cousin of Virginia's largest landowner, Thomas, Lord Fairfax, was also a formative influence. Washington spent much of his boyhood at Ferry Farm in Stafford County near Fredericksburg. Lawrence Washington inherited another family property from his father, a plantation on the Potomac River which he later named Mount Vernon. George inherited Ferry Farm upon his father's death, and eventually acquired Mount Vernon after Lawrence's death.[11]

At age 16, Washington drew this practice survey of half-brother Lawrence's turnip field at Mount Vernon.

The death of his father prevented Washington from crossing the Atlantic to receive an education at England's Appleby School, as his older brothers had done. He attended school in Fredericksburg until age 15. Talk of securing an appointment in the Royal Navy were dropped when his mother learned how hard that would be on him.[12] Late in life, Washington was somewhat self-conscious that he was less educated than those of his contemporaries who had attended college. Thanks to Lawrence's connection to the powerful Fairfax family, at age 17 George was appointed official surveyor for Culpeper County in 1749, a well-paid position which enabled him to purchase land in the Shenandoah Valley, the first of his many land acquisitions in western Virginia. Thanks also to Lawrence's involvement in the Ohio Company, a land investment company funded by Virginia investors, and Lawrence's position as commander of the Virginia militia, George came to the notice of the new lieutenant governor of Virginia, Robert Dinwiddie. Washington was hard to miss: at about six feet two inches (188 cm; estimates of his height vary), he towered over most of his contemporaries.[13]

In 1751, Washington traveled to Barbados with Lawrence, who was suffering from tuberculosis, with the hope that the climate would be beneficial to Lawrence's health. Washington contracted smallpox during the trip, which left his face slightly scarred, but immunized him against future exposures to the dreaded disease.[14] Lawrence's health did not improve: he returned to Mount Vernon, where he died in 1752.[15] Lawrence's position as Adjutant General (militia leader) of Virginia was divided into four offices after his death. Washington was appointed by Governor Dinwiddie as one of the four district adjutants in February 1753, with the rank of major in the Virginia militia.[16] Washington also joined the Freemasons in Fredericksburg at this time.[17]

French and Indian War (Seven Years War) (1754–1758)

Main article: George Washington in the French and Indian War

See also: Battle of Jumonville Glen, Battle of the Great Meadows, Braddock expedition, and Battle of Fort Duquesne

Washington's 1754 map showing Ohio River and surrounding region

In 1753 the French began expanding their military control into the "Ohio Country", a territory also claimed by the British colonies of Virginia and Pennsylvania. These competing claims led to a world war 1756–63 (called the French and Indian War in the colonies and the Seven Years' War in Europe) and Washington was at the center of its beginning. The Ohio Company was one vehicle through which British investors planned to expand into the territory, opening new settlements and building trading posts for the Indian trade. Governor Dinwiddie received orders from the British government to warn the French of British claims, and sent Major Washington in late 1753 to deliver a letter informing the French of those claims and asking them to leave.[18] Washington also met with Tanacharison (also called "Half-King") and other Iroquois leaders allied to Virginia at Logstown to secure their support in case of conflict with the French; Washington and Half-King became friends and allies. Washington delivered the letter to the local French commander, who politely refused to leave.[19]

Governor Dinwiddie sent Washington back to the Ohio Country to protect an Ohio Company group building a fort at present-day Pittsburg, Pennsylvania. Before he reached the area, a French force drove out the company's crew and began construction of Fort Duquesne. With Mingo allies led by Tanacharison, Washington and some of his militia unit ambushed a French scouting party of some 30 men, led by Joseph Coulon de Jumonville; Jumonville was killed.[20] The French responded by attacking and capturing Washington at Fort Necessity in July 1754.[21] He was allowed to return with his troops to Virginia. The episode demonstrated Washington's bravery, initiative, inexperience and impetuosity.[22][23] These events had international consequences; the French accused Washington of assassinating Jumonville, who they claimed was on a diplomatic mission similar to Washington's 1753 mission.[24] Both France and Britain responded by sending troops to North America in 1755, although war was not formally declared until 1756.

Braddock disaster 1755

In 1755, Washington was the senior American aide to British General Edward Braddock on the ill-fated Monongahela expedition. This was the largest British expedition to the colonies, and was intended to expel the French from the Ohio Country. The French and their Indian allies ambushed Braddock, who was mortally wounded in the Battle of the Monongahela. After suffering devastating casualties the British retreated in disarray but Washington rode back and forth across the battlefield, rallying the remnants of the British and Virginian forces to an organized retreat.[25]

Commander of Virginia Regiment

This 1772 painting by Peale of Washington as colonel of the Virginia Regiment, is the earliest known portrait

Governor Dinwiddie rewarded Washington in 1755 with a commission as "Colonel of the Virginia Regiment and Commander in Chief of all forces now raised in the defense of His Majesty's Colony" and gave him the task of defending Virginia's frontier. The Virginia Regiment was the first full-time American military unit in the colonies (as opposed to part-time militias and the British regular units). Washington was ordered to "act defensively or offensively" as he thought best.[26] In command of a thousand soldiers, Washington was a disciplinarian who emphasized training. He led his men in brutal campaigns against the Indians in the west; in 10 months units of his regiment fought 20 battles, and lost a third of its men. Washington's strenuous efforts meant that Virginia's frontier population suffered less than that of other colonies; Ellis concludes "it was his only unqualified success" in the war.[27][28]

In 1758, Washington participated in the Forbes expedition to capture Fort Duquesne. He was embarrassed by a friendly fire episode in which his unit and another British unit thought the other was the French enemy and opened fire, with 14 dead and 26 wounded in the mishap. In the end there was no real fighting for the French abandoned the fort and the British scored a major strategic victory, gaining control of the Ohio Valley. Mission accomplished, Washington retired from his Virginia Regiment commission in December, 1758, and did not return to military life until the outbreak of the revolution in 1775.[29]

Lessons learned

Although Washington never gained the commission in the British army he yearned for, in these years the young man gained valuable military, political, and leadership skills.[30] He closely observed British military tactics, gaining a keen insight into their strengths and weaknesses that proved invaluable during the Revolution. He demonstrated his toughness and courage in the most difficult situations, including disasters and retreats. He developed a command presence—given his size, strength, stamina, and bravery in battle, he appeared to soldiers to be a natural leader and they followed him without question.[31][32] Washington learned to organize, train, drill, and discipline his companies and regiments. From his observations, readings and conversations with professional officers, he learned the basics of battlefield tactics, as well as a good understanding of problems of organization and logistics.[33] He gained an understanding of overall strategy, especially in locating strategic geographical points.[34] His frustrations in dealing with government officials led him to stress the advantage of a strong national government, and a vigorous executive agency that could get results; his dealings gave him the diplomatic skills necessary to negotiate with officials at the local and colonial levels.[35] He developed a very negative idea of the value of militia, who seemed too unreliable, too undisciplined, and too short-term compared to regulars.[36] On the other hand, his experience was limited to command of at most 1000 men, and came only in remote frontier conditions that were far removed from the urban situations he faced during the Revolution at Boston, New York, Trenton and Philadelphia.[37]

Between the wars: Mount Vernon (1759–1774)

A mezzotint of Martha Washington, based on a 1757 portrait by Wollaston

On January 6, 1759, Washington married the wealthy widow Martha Dandridge Custis. Surviving letters suggest that he may have been in love at the time with Sally Fairfax, the wife of a friend.[38] Nevertheless, George and Martha made a compatible marriage, since Martha was intelligent, gracious, and experienced in managing a slave plantation.[39] Together the two raised her two children from her previous marriage, John Parke Custis and Martha Parke Custis, affectionately called "Jackie" and "Patsy" by the family. Later the Washingtons raised two of Mrs. Washington's grandchildren, Eleanor Parke Custis and George Washington Parke Custis. George and Martha never had any children together — his earlier bout with smallpox in 1751 may have made him sterile. Washington, himself, an extraordinary athlete, proudly may not have been able to admit to his own sterility while privately he grieved over not having his own children.[40] The newly wed couple moved to Mount Vernon, near Alexandria, where he took up the life of a planter and political figure.

Washington's marriage to Martha greatly increased his property holdings and social standing, and made him one of Virginia's wealthiest men. He acquired one-third of the 18,000 acre (73 km²) Custis estate upon his marriage, worth approximately $100,000, and managed the remainder on behalf of Martha's children, for whom he sincerely cared.[41] He frequently bought additional land in his own name and was granted land in what is now West Virginia as a bounty for his service in the French and Indian War. By 1775, Washington had doubled the size of Mount Vernon to 6,500 acres (26 km2), and had increased the slave population there to more than 100 persons. As a respected military hero and large landowner, he held local office and was elected to the Virginia provincial legislature, the House of Burgesses, beginning in 1758.[42]

Washington enlarged the house at Mount Vernon after his marriage

Washington lived an aristocratic lifestyle—fox hunting was a favorite leisure activity.[43] He also enjoyed going to dances and parties, in addition to the theater, races, and cock fights. Washington also was known to play cards, backgammon, and billiards.[44] Like most Virginia planters, he imported luxuries and other goods from England and paid for them by exporting his tobacco crop. Extravagant spending and the unpredictability of the tobacco market meant that many Virginia planters of Washington's day were losing money. (Thomas Jefferson, for example, would die deeply in debt.)

Washington began to pull himself out of debt by diversification.[45] By 1766, he had switched Mount Vernon's primary cash crop from tobacco to wheat, a crop that could be sold in America, and diversified operations to include flour milling, fishing, horse breeding, spinning, and weaving. Patsy Custis's death in 1773 from epilepsy enabled Washington to pay off his British creditors, since half of her inheritance passed to him.[46]

A successful planter, he was a leader in the social elite in Virginia. From 1768 to 1775, he invited some 2000 guests to his Mount Vernon estate, mostly those he considered "people of rank." As for people not of high social status, his advice was to "treat them civilly" but "keep them at a proper distance, for they will grow upon familiarity, in proportion as you sink in authority.".[47] In 1769 he became more politically active, presenting the Virginia Assembly with legislation to ban the importation of goods from Great Britain.[48]

American Revolution (1775–1787)

Main article: George Washington in the American Revolution

Forensic reconstruction of Washington at age 45

Although he expressed opposition to the 1765 Stamp Act, the first direct tax on the colonies, he did not take a leading role in the growing colonial resistance until protests of the Townshend Acts (enacted in 1767) became widespread. In May 1769, Washington introduced a proposal, drafted by his friend George Mason, calling for Virginia to boycott English goods until the Acts were repealed.[49] Parliament repealed the Townshend Acts in 1770, and, for Washington at least, the crisis had passed. However, Washington regarded the passage of the Intolerable Acts in 1774 as "an Invasion of our Rights and Privileges".[50] In July 1774, he chaired the meeting at which the "Fairfax Resolves" were adopted, which called for, among other things, the convening of a Continental Congress. In August, Washington attended the First Virginia Convention, where he was selected as a delegate to the First Continental Congress.[51]

Commander in chief

After the Battles of Lexington and Concord near Boston in April 1775, the colonies went to war. Washington appeared at the Second Continental Congress in a military uniform, signaling that he was prepared for war.[52] Washington had the prestige, military experience, charisma and military bearing of a military leader and was known as a strong patriot. Virginia, the largest colony, deserved recognition, and New England—where the fighting began—realized it needed Southern support. Washington he did not explicitly seek the office of commander and said that he was not equal to it, but there was no serious competition.[53] Congress created the Continental Army on June 14, 1775. Nominated by John Adams of Massachusetts, Washington was then appointed Major General and Commander-in-chief.[54]

Washington had three roles during the war. In 1775-77, and again in 1781 he led his men against the main British forces. He lost many of his battles—save the last one—but always survived to fight another day. He plotted the overall strategy of the war, in cooperation with Congress.

Second he was charged with organizing and training the army. He recruited regulars and assigned General von Steuben, a German professional, to train them. He was not in charge of supplies, which were always short, but kept pressuring Congress and the states to provide essentials.[55] Washington had the major voice in selecting generals for command, and in planning their basic strategy. His achievements were mixed, as some of his favorites (like John Sullivan) never mastered the art of command. Eventually he found men who got the job done, like General Nathaniel Greene, and his chief-of-staff Alexander Hamilton. The American officers never equaled their opponents in tactics and maneuver, and consequently they lost most of the pitched battles. The great successes, at Saratoga and Yorktown, came from trapping the British far from base with much larger numbers of troops.

Third, and most important, Washington was the embodiment of armed resistance to the Crown—the representative man of the Revolution. His enormous stature and political skills kept Congress, the army, the French, the militias, and the states all pointed toward a common goal. By voluntarily stepping down and disbanding his army when the war was won, he permanently established the principle of civilian supremacy in military affairs. And yet his constant reiteration of the point that well-disciplined professional soldiers counted for twice as much as erratic amateurs helped overcome the ideological distrust of a standing army.

Victory at Boston

Washington assumed command of the Continental Army in the field at Cambridge, Massachusetts in July 1775, during the ongoing siege of Boston. Realizing his army's desperate shortage of gunpowder, Washington asked for new sources. American troops raided British arsenals, including some in the Caribbean, and some manufacturing was attempted. They obtained a barely adequate supply (about 2.5 million pounds) by the end of 1776, mostly from France.[56] Washington reorganized the army during the long standoff, and forced the British to withdraw by putting artillery on Dorchester Heights overlooking the city. The British evacuated Boston in March 1776 and Washington moved his army to New York City.

Although highly disparaging toward most of the Patriots, British newspapers routinely praised Washington's personal character and qualities as a military commander. These articles were bold, as Washington was enemy general who commanded an army in a cause that many Britons believed would ruin the empire.[57]

Defeat at New York City and Fabian tactics

In August 1776, British General William Howe launched a massive naval and land campaign designed to seize New York. The Continental Army under Washington engaged the enemy for the first time as an army of the newly independent United States at the Battle of Long Island, the largest battle of the entire war. The Americans were badly outnumbered, many men deserted, and Washington was badly beaten. Historian David McCullough has portrayed the army's subsequent night time retreat across the East River, without the loss of a single life or materiel, as one of Washington's greatest military feats.[58][page needed] Washington retreated north from the city to avoid encirclement, enabling Howe to take the offensive and capture Fort Washington on November 16 with high Continental casualties. Washington then retreated across New Jersey; the future of the Continental Army was in doubt due to expiring enlistments and the string of losses. On the night of December 25, 1776, Washington staged a comeback with a surprise attack on a Hessian outpost in western New Jersey. He led his army across the Delaware River to capture nearly 1,000 Hessians in Trenton, New Jersey. Washington followed up his victory at Trenton with another over British regulars at Princeton in early January. The British retreated back to New York City and its environs, which they held until the peace treaty of 1783. Washington's victories wrecked the British carrot-and-stick strategy of showing overwhelming force then offering generous terms. The Americans would not negotiate for anything short of independence.[59] These victories alone were not enough to ensure ultimate Patriot victory, however, since many soldiers did not reenlist or deserted during the harsh winter. Washington and Congress reorganized the army with increased rewards for staying and punishment for desertion, which raised troop numbers effectively for subsequent battles.[60]

Washington rallying his troops at the Battle of Princeton

Historians debate whether or not Washington preferred a Fabian strategy[61] to harass the British, with quick shark attacks followed by a retreat so the larger British army could not catch him, or whether he preferred to fight major battles.[62] While his southern commander Greene in 1780-81 did use Fabian tactics, Washington, only did so in fall 1776 to spring 1777, after losing New York City and seeing much of his army melt away. Trenton and Princeton were Fabian examples. By summer 1777, however, Washington had rebuilt his strength and his confidence and stopped using raids and went for large-scale confrontations, as at Brandywine, Germantown, Monmouth and Yorktown.[63]

1777 campaigns

In the late summer of 1777 the British under John Burgoyne sent a major invasi