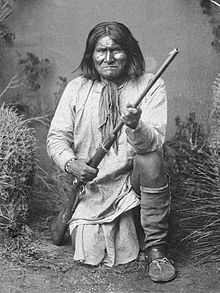

Chief of the Chiricahua Apache, Geronimo

For other uses, see Geronimo (disambiguation).

| Geronimo |

|

| Born |

Goyahkla, Goyaałé: "one who yawns"

June 16, 1829

Gila River, New Mexico (modern-day) |

| Died |

February 17, 1909 (aged 79)

Fort Sill, Oklahoma |

| Known for |

A famous Apache warrior |

Geronimo (Chiricahua: Goyaałé, "one who yawns"; often spelled Goyathlay or Goyahkla[1] in English) (June 16, 1829 – February 17, 1909) was a prominent Native American leader of the Chiricahua Apache who fought against Mexico and the United States and their expansion into Apache tribal lands for several decades during the Apache Wars.

[edit] Biography

Geronimo as a U.S. prisoner in 1909

Goyahkla (Geronimo) was born to the Bedonkohe band of the Apache, near Turkey Creek, a tributary of the Gila River in the modern-day state of New Mexico, then part of Mexico, but which his family considered Bedonkohe land. His grandfather (Mako) had been chief of the Bedonkohe Apache. He had three brothers and four sisters.[2]

Geronimo's parents raised him according to Apache traditions; after the death of his father, his mother took him to live with the Chihenne (red paint people) and he grew up with them. He married a woman (Alope) from the Nedni-Chiricahua band of Apache when he was 17; they had three children. On March 6, 1858, a company of 400 Mexican soldiers from Sonora led by Colonel José MarÃa Carrasco attacked Geronimo's camp outside Janos while the men were in town trading. Among those killed were Geronimo's wife, his children, and his mother. His chief, Mangas Coloradas, sent him to Cochise's band for help in revenge against the Mexicans. It was the Mexicans who named him Geronimo. This appellation stemmed from a battle in which, ignoring a deadly hail of bullets, he repeatedly attacked Mexican soldiers with a knife, causing them to utter appeals to Saint Jerome ("Jeronimo!"). The name stuck.[1]

The first Apache raids on Sonora and Chihuahua appear to have taken place during the late 17th century. To counter the early Apache raids on Spanish settlements, presidios were established at Janos (1685) in Chihuahua and at Fronteras (1690) in northern Opata country. In 1835, Mexico had placed a bounty on Apache scalps. Two years later Mangas Coloradas or Dasoda-hae (Red Sleeves) became principal chief and war leader and began a series of retaliatory raids against the Mexicans. Apache raids on Mexican villages were so numerous and brutal that no area was safe.[3]

While Geronimo said he was never a chief, he was a military leader. As a Chiricahua Apache, this meant he was one of many people with special spiritual insights and abilities known to Apache people as "Power". Among these were the ability to walk without leaving tracks; the abilities now known as telekinesis and telepathy; and the ability to survive gunshot (rifle/musket, pistol, and shotgun). Geronimo was wounded numerous times by both bullets and buckshot, but survived. Apache men chose to follow him of their own free will, and offered first-hand eye-witness testimony regarding his many "powers". They declared that this was the main reason why so many chose to follow him: they thought he was favored or protected by "Usen", the Apache high-god. Geronimo's "powers" were considered to be so great that he personally painted the faces of the warriors who followed him to reflect their protective effect. During his career as a war chief, Geronimo was notorious for consistently urging raids and war upon Mexican Provinces and their various towns, and later against American locations across Arizona, New Mexico, and western Texas.[4]

He married Chee-hash-kish and had two children, Chappo and Dohn-say. Then he took another wife, Nana-tha-thtith, with whom he had one child.[5] He later had a wife named Zi-yeh at the same time as another wife, She-gha, one named Shtsha-she and later a wife named Ih-tedda. Some of his wives were captured, such as the young Ih-tedda. Wives came and went, overlapping each other, being captured and added to the family, lost, or even given up, as Geronimo did with Ih-tedda when he and his band surrendered. At that time he kept his wife She-gha but abandoned the younger wife, Ih-tedda. Geronimo's last wife was Azul.

Ta-ayz-slath, wife of Geronimo, and child

Though outnumbered, Geronimo fought against both Mexican and United States troops and became famous for his daring exploits and numerous escapes from capture from 1858 to 1886. One such escape, as legend has it, took place in the Robledo Mountains of southwest New Mexico. The legend states Geronimo and his followers entered a cave, and the U.S. soldiers waited outside the cave entrance for him, but he never came out. Later it was heard that Geronimo was spotted in a nearby area. The second entrance to the cave has yet to be found and the cave is still called Geronimo's Cave. At the end of his military career, he led a small band of 36 men, women, and children. They evaded thousands of Mexican and American troops for over a year, making him the most famous Native American of the time and earning him the title of the "worst Indian who ever lived" among white settlers.[6] His band was one of the last major forces of independent Native American warriors who refused to acknowledge the United States occupation of the American West.

[edit] Pursuit and surrender

In 1886, General Nelson A. Miles selected Captain Henry Lawton, in command of B Troop, 4th Cavalry, at Ft. Huachuca and First Lieutenant Charles B. Gatewood to lead the expedition that captured Geronimo.[7] Numerous stories abound as to who actually captured Geronimo, or to whom he surrendered, although most contemporary accounts, and Geronimo's own later statements, give most of the credit for negotiating the surrender to Lt. Gatewood. For Lawton's part, he was given orders to head up actions south of the U.S.–Mexico boundary where it was thought Geronimo and a small band of his followers would take refuge from U.S. authorities.[7] Lawton was to pursue, subdue, and return Geronimo to the U.S., dead or alive.[7]

Lawton's official report dated September 9, 1886 sums up the actions of his unit and gives credit to a number of his troopers for their efforts. Geronimo gave Gatewood credit for his decision to surrender as Gatewood was well known to Geronimo, spoke some Apache, and was familiar with and honored their traditions and values. He acknowledged Lawton's tenacity for wearing the Apaches down with constant pursuit. Geronimo and his followers had little or no time to rest or stay in one place. Completely worn out, the little band of Apaches returned to the U.S. with Lawton and officially surrendered to General Miles on September 4, 1886 at Skeleton Canyon, Arizona.[7]

When Geronimo surrendered he had in his possession a Winchester Model 1876 lever-action rifle with a silver-washed barrel and receiver, bearing Serial Number 109450. It is on display at the United States Military Academy, West Point, New York. Additionally he had a Colt Single Action Army revolver with a nickel finish and ivory stocks bearing the serial number 89524 and a Sheffield Bowie knife with a dagger type of blade and stag handle made by George Wostenholm in an elaborate silver-studded holster and cartridge belt. The revolver, rig, and knife are on display at the Fort Sill museum.[8]

The debate still remains whether Geronimo surrendered unconditionally. Geronimo pleaded in his memoirs that his people who surrendered had been misled: his surrender as a war prisoner was conditioned in front of uncontested witnesses (especially General Stanley). General Howard, chief of Pacific US army division, said on his part that his surrender was accepted as a dangerous outlaw without condition, which has been contested in front of the Senate.

[edit] Prisoner of war

Geronimo and other Apaches, including the Apache scouts who had helped the army track him down, were sent as prisoners to Fort Pickens, in Pensacola, Florida, and his family was sent to Fort Marion.[9] They were reunited in May 1887, when they were transferred to Mount Vernon Barracks in Alabama for seven years. In 1894, they were moved to Fort Sill, Oklahoma. In his old age, Geronimo became a celebrity. He appeared at fairs, including the 1904 World's Fair in St. Louis, where he reportedly rode a ferris wheel and sold souvenirs and photographs of himself. However, he was not allowed to return to the land of his birth. He rode in President Theodore Roosevelt's 1905 inaugural parade.[10]

In 1905, Geronimo agreed to tell his story to S. M. Barrett, Superintendent of Education in Lawton, Oklahoma. Barrett had to appeal to President Roosevelt to gain permission to publish the book. Geronimo came to each interview knowing exactly what he wanted to say. He refused to answer questions or alter his narrative. Barrett did not seem to take many liberties with Geronimo's story as translated by Asa Daklugie. Frederick Turner re-edited this autobiography by removing some of Barrett's footnotes and writing an introduction for the non-Apache readers. Turner notes the book is in the style of an Apache reciting part of his oral history.[10][not in citation given]

In February 1909, Geronimo was thrown from his horse while riding home, and had to lie in the cold all night before a friend found him extremely ill.[6] He died of pneumonia on February 17, 1909, as a prisoner of the United States at Fort Sill, Oklahoma.[11] On his deathbed, he confessed to his nephew that he regretted his decision to surrender.[6] He was buried at Fort Sill in the Apache Indian Prisoner of War Cemetery.[7]

[edit] Religion

Apache leader Geronimo (right) is depicted with a small group of followers in northern Mexico in 1886

Geronimo was raised with the traditional religious views of the Bedonkohe. When questioned about his views on life after death, he wrote in his 1905 autobiography, "As to the future state, the teachings of our tribe were not specific, that is, we had no definite idea of our relations and surroundings in after life. We believed that there is a life after this one, but no one ever told me as to what part of man lived after death ... We held that the discharge of one's duty would make his future life more pleasant, but whether that future life was worse than this life or better, we did not know, and no one was able to tell us. We hoped that in the future life, family and tribal relations would be resumed. In a way we believed this, but we did not know it."[12]

Later in life, Geronimo embraced Christianity, and stated, "Since my life as a prisoner has begun I have heard the teachings of the white man's religion, and in many respects believe it to be better than the religion of my fathers ... Believing that in a wise way it is good to go to church, and that associating with Christians would improve my character, I have adopted the Christian religion. I believe that the church has helped me much during the short time I have been a member. I am not ashamed to be a Christian, and I am glad to know that the President of the United States is a Christian, for without the help of the Almighty I do not think he could rightly judge in ruling so many people. I have advised all of my people who are not Christians, to study that religion, because it seems to me the best religion in enabling one to live right."[13] He joined the Dutch Reformed Church in 1903 but four years later was expelled for gambling.[13] To the end of his life, he seemed to harbor ambivalent religious feelings, telling the Christian missionaries at a summer camp meeting in 1908 that he wanted to start over, while at the same time telling his tribesmen that he held to the old Apache religion.[14]

[edit] Alleged theft of skull

Portrait of Geronimo by Edward S. Curtis, 1905.

Six members of the Yale secret society of Skull and Bones, including Prescott Bush, served as Army volunteers at Fort Sill during World War I. It has been claimed by various parties that they stole Geronimo's skull, some bones, and other items, including Geronimo's prized silver bridle, from the Apache Indian Prisoner of War Cemetery at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. Alexandra Robbins says this is one of the more plausible items said to be in the organization's Tomb.[15]

In 1986, former San Carlos Apache Chairman Ned Anderson received an anonymous letter with a photograph and a copy of a log book claiming that Skull & Bones held the skull. He met with Skull & Bones officials about the rumor; the group's attorney, Endicott P. Davidson, denied that the group held the skull, and said that the 1918 ledger saying otherwise was a hoax.[16] The group offered Anderson a glass case containing what appeared to be the skull of a child, but Anderson refused it.[17] In 2006, Marc Wortman discovered a 1918 letter from Skull & Bones member Winter Mead to F. Trubee Davison that claimed the theft:[18]

- The skull of the worthy Geronimo the Terrible, exhumed from its tomb at Fort Sill by your club... is now safe inside the tomb and bone together with his well worn femurs, bit and saddle horn.[18]

The second "tomb" references is the building of Yale University's Skull and Bones society.

But Mead was not at Fort Sill, and Cameron University history professor David H. Miller notes that Geronimo's grave was unmarked at the time.[18] The revelation led Harlyn Geronimo of Mescalero, New Mexico, to write to President Bush requesting his help in returning the remains:

- According to our traditions the remains of this sort, especially in this state when the grave was desecrated ... need to be reburied with the proper rituals ... to return the dignity and let his spirits rest in peace.[19]

Geronimo's grave at Fort Sill, Oklahoma in 2005.

In 2009, Ramsey Clark filed a lawsuit on behalf of people claiming to be Geronimo's descendants, against, among others, Barack Obama, Robert Gates, and Skull and Bones, asking for the return of Geronimo's bones.[16] An article in The New York Times states that Clark "acknowledged he had no hard proof that the story was true."[20]

Investigators ranging from Cecil Adams to Kitty Kelley have rejected the story.[2][21] A Fort Sill spokesman told Adams, "There is no evidence to indicate the bones are anywhere but in the grave site."[2] Jeff Houser, chairman of the Fort Sill Apache tribe of Oklahoma, calls the story a hoax.[17]

[edit] Popular culture

501st Infantry Regiment Distinctive Unit Insignia

- The 501st Parachute Infantry Regiment's motto and slogan was named after him. In 1940, the night before their first mass jump, U.S. paratroopers at Fort Benning watched the 1939 film Geronimo, in which the actor playing Geronimo yells his name as he leaps from a high cliff into a river, depicting a real-life escape Geronimo successfully attempted in which he jumped off Medicine Bluff at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, into the Medicine Creek with his Cadillac horse. Private Aubrey Eberhardt announced he would shout the name when he jumped from the airplane to prove he was not scared. The trend has since caught on elsewhere, becoming widely associated with any sort of high jump in popular culture. This unit was the first parachute battalion of the United States Army.[22][23]

- In George MacDonald Fraser's novel, Flashman and the Redskins, the anti-hero Flashman meets Geronimo when he is captured by a band of Apaches lead by Mangas Coloradas. He later claims Geronimo as his one and only Red Indian friend.

- In 1943, a U.S. Liberty ship named the SS Geronimo was launched. It was scrapped in 1960.

- Three towns in the United States are named for him: one in Arizona, one in Oklahoma, and another in Texas.

- Singer-songwriter Michael Murphey released an album (and single), "Geronimo's Cadillac", in 1972.

- German band Modern Talking released as a single in 1986 a song named "Geronimo's Cadillac".

[edit] Movies & television

Geronimo is a popular figure in cinema and television. Characters based on Geronimo have appeared in many films, including:

- Geronimo's Last Raid (1912)

- Hawk of the Wilderness (1938)

- Geronimo (1939 film) (1939)

- Stagecoach (1939)

- Valley of the Sun (1942)

- Fort Apache (1948)

- Broken Arrow (1950)

- I Killed Geronimo (1950)

- The Last Outpost (1951)

- Son of Geronimo (1952)

- The Battle at Apache Pass (1952)

- Indian Uprising (1952)

- Apache (1954)

- Taza, Son of Cochise (1954)

- Walk the Proud Land (1956)

- Geronimo (1962 film) (1962)

- Geronimo und die Räuber (West German, 1966)

- I Due superpiedi quasi piatti (1976)

- Mr. Horn (1979)

- Gunsmoke: The Last Apache (1990)

- Geronimo: An American Legend (1993)

- Geronimo (TV film) (starring Joseph Runningfox) (1993)

In 1954, Chief Yowlachie (1891–1966) appeared as Geronimo in an episode of the same name of Jim Davis's syndicated western television series, Stories of the Century. John Doucette played the role of Geronimo on the syndicated series Death Valley Days and in three segments of Tombstone Territory, starring with Pat Conway and Richard Eastham.

Geronimo's life is described and dramatised in Episode 4 of the 2009 Ric Burns/American Experience documentary We Shall Remain.

[edit] References

- ^ a b "Geronimo". National Geographic Magazine 182: 52. October 1992.

- ^ a b c Adams, Alexander B. (1990). Geronimo: a Biography. Da Capo Press. pp. 391. ISBN 978-0306803949.

- Apache Indians Southwest

- Ball, Eve "Indeh: An Apache Odyssey". University of Oklahoma Press. 1988. ISBN 0-8061-2165-3

- "Wives and burial place of Geronimo". http://www.aaanativearts.com/apache/geronimo-wives-burial-place.htm. Retrieved 2009-09-04.

- ^ a b c "The American Experience, We Shall Remain: Geronimo". http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/weshallremain/the_films/episode_4_trailer. Retrieved November 12, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Capps, Benjamin (1975). The Great Chiefs. Time-Life Education. pp. 240. ISBN 978-0316847858.

- Herring, Hal (2008). Famous Firearms of the Old West: From Wild Bill Hickok's Colt Revolvers to Geronimo's Winchester, Twelve Guns That Shaped Our History. TwoDot. pp. 224. ISBN 0762745088.

- "Gulf Islands National Seashore - The Apache (U.S. National Park Service)". nps.gov. http://www.nps.gov/guis/historyculture/the-apache.htm. Retrieved 2009-05-24

- ^ a b Barrett, Stephen Melvil and Turner, Frederick W. (1970), Introduction, Geronimo: His Own Story: The Autobiography of a Great Patriot Warrior, Dutton, New York, ISBN 0-525-11308-8 ;

- Death of Geronimo, History Today

- Geronimo (S. M. Barrett, Editor) (1971). Geronimo, His Own Story. New York, New York: Ballantine Books. LCCCN 72-113457. ISBN 0349102600. page 178

- ^ a b Geronimo (S. M. Barrett, Editor) (1971). Geronimo, His Own Story. New York, New York: Ballantine Books. LCCCN 72-113457. ISBN 0349102600. page 181

- Debo, Angie (1976). Geronimo, The Man, His Time, His Place. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. LCCCN 0-8061-1828-8. ISBN 0806113332. pages 437–438

- Geronimo's kin sue Skull and Bones over remains

- ^ a b Daniels, Bruce (February 27, 2009). "Geronimo Lawsuit Sparks Family Feud". Albuquerque Journal. http://www.abqjournal.com/abqnews/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=10846:635am-geronimo-died-100-years-ago-today&catid=1:latest&Itemid=39. Retrieved 2009-02-28.

- ^ a b Pember, Mary Annette (July 9, 2007). "Tomb Raiders". Diverse Issues in Higher Education. http://www.diverseeducation.com/artman/publish/article_8184.shtml. Retrieved 2009-02-28.

- ^ a b c Lassila, Kathrin Day; Mark Alden Branch (May/June 2006). "Whose Skull and Bones?". Yale Alumni Magazine. http://www.yalealumnimagazine.com/issues/2006_05/notebook.html. Retrieved 2009-02-28.

- Andrew Buncombe (June 1, 2006). "Geronimo's family call on Bush to help return his skeleton". London: The Independent. http://news.independent.co.uk/world/americas/article622744.ece. Retrieved December 5, 2006.

- Geronimo’s Heirs Sue Secret Yale Society Over His Skull

- Kelley, Kitty (2004). The Family: The Real Story of the Bush Dynasty. Doubleday. pp. 17–20. ISBN 0385503245.

- Anderson, Chuck (September 2004). "Geronimo yell of World War II paratroopers". B-Westerns.com. http://www.b-westerns.com/geronimo.htm. Retrieved 2007-10-15.

- Adams, Cecil (1998-01-23). "Why do parachutists yell "Geronimo!" when jumping from an airplane?". The Straight Dope. http://www.straightdope.com/classics/a5_146.html. Retrieved 2007-10-15.

[edit] Further reading

- Geronimo's Story of His Life; as told to Stephen Melvil Barrett. Published: New York, Duffield & Company, 1906. Online at Webroots; Edition Oct 15 2002

- Geronimo (edited by Barrett) "Geronimo, His Own Story" New York: Ballantine Books 1971. ISBN 0345280369. Also ISBN 0850521041

- Carter, Forrest. "Watch for Me on the Mountain". Delta. 1990. (Originally entitled "Cry Geronimo".)

- Opler, Morris E.; & French, David H. (1941). Myths and tales of the Chiricahua Apache Indians. Memoirs of the American folk-lore society, (Vol. 37). New York: American Folk-lore Society. (Reprinted in 1969 by New York: Kraus Reprint Co.; in 1970 by New York; in 1976 by Millwood, NY: Kraus Reprint Co.; & in 1994 under M. E. Opler, Morris by Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-8602-3).

- Pinnow, Jürgen. (1988). Die Sprache der Chiricahua-Apachen: Mit Seitenblicken auf das Mescalero [The language of the Chiricahua Apache: With side glances at the Mescalero]. Hamburg: Helmut Buske Verlag.

- Davis, Britton "The Truth about Geronimo" New Haven: Yale Press 1929

- Bigelow, John Lt "On the Bloody Trail of Geronimo" New York: Tower Books 1958

- Debo, Angie. Geronimo: The Man, His Time, His Place. University of Oklahoma Press : Norman, 1976

- Pember, Mary Annette. (July 12, 2007). "'Tomb Raiders': Yale's ultra-secret Skull and Bones Society is believed to possess the skull of legendary Apache chief Geronimo." Diverse Issues in Higher Education 24(11), 10–11. Retrieved April 23, 2008.[1]

- Faulk, Odie B. The Geronimo Campaign. Oxford University Press: New York, 1969. ISBN 0-19-508351-2

- Dee Brown, Bury my Heart at Wounded Knee. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1970. ISBN 0030853222

[edit] External links