Coues, Elliot

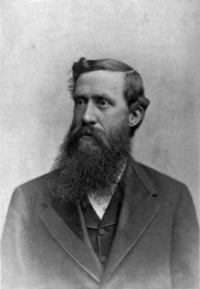

| Elliott Coues |

Elliott Coues

|

| Born |

September 9, 1842

Portsmouth, New Hampshire |

| Died |

December 25, 1899 |

| Nationality |

American |

| Institutions |

ornithology |

| Alma mater |

Columbian University |

Elliott Coues (September 9, 1842 – December 25, 1899) was an American army surgeon, historian, ornithologist and author.[1]

Coues (pronounced /ˈkaʊz/) was born in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. He graduated at Columbian University, (now, George Washington University) Washington, D.C., in 1861, and at the Medical school of that institution in 1863. He served as a medical cadet in Washington in 1862-1863, and in 1864 was appointed assistant-surgeon in the regular army. In 1872 he published his Key to North American Birds, which, revised and rewritten in 1884 and 1901, did much to promote the systematic study of ornithology in America. His work was instrumental in establishing the currently accepted standards of trinomial nomenclature - the taxonomic classification of subspecies - in ornithology, and ultimately the whole of zoology. In 1873-1876 Coues was attached as surgeon and naturalist to the United States Northern Boundary Commission, and in 1876-1880 was secretary and naturalist to the United States Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories, the publications of which he edited. He was lecturer on anatomy in the medical school of the Columbian University in 1877-1882, and professor of anatomy there in 1882-1887.

He was a careful bibliographer and in his work on the Birds of the Colorado Valley he included a special section on swallows and attempted to resolve whether they migrated in winter or hibernated under lakes as was believed at the time:

I have never seen anything of the sort, nor have I ever known one who had seen it; consequently, I know nothing of the case but what I have read about it. But I have no means of refuting the evidence, and consequently cannot refuse to recognize its validity. Nor have I aught to urge against it, beyond the degree of incredibility that attaches to highly exceptional and improbable allegations in general, and in particular the difficulty of understanding the alleged abruptness of the transition from activity to torpor. I cannot consider the evidence as inadmissible, and must admit that the alleged facts are as well attested, according to ordinary rules of evidence, as any in ornithology. It is useless as well as unscientific to pooh-pooh the notion. The asserted facts are nearly identical with the known cases of many reptiles and batrachians. They are strikingly like the known cases of many bats. They accord in general with the recognized conditions of hibernation in many mammals.

—Birds of the Colorado Valley (1878), Chapter XIV.

[2]

He resigned from the army in 1881 to devote himself entirely to scientific research. He was a founder of the American Ornithologists' Union, and edited its organ, The Auk, and several other ornithological periodicals. He died in Baltimore, Maryland.

In addition to ornithology he did valuable work in mammalogy; his book Fur-Bearing Animals (1877) being distinguished by the accuracy and completeness of its description of species, several of which were already becoming rare. Coues Deer are named after him.

He took an interest in spiritualism and began speculations in theosophy. He felt the inadequacy of formal orthodox science in dealing with the deeper problems of human life and destiny. Convinced by the principles of evolution, he believed that these principles may be capable of being applied in psychic research and he proposed to use it to explain obscure phenomena such as hypnotism, clairvoyance, telepathy and the like. For this he visited Madame Blavatsky in Europe. He then founded the Gnostic Theosophical Society of Washington, and in 1890 he became the president of the Esoteric Theosophical Society of America. Around this time he also exposed Blavatsky and lost his interest in the theosophical movement.[3]

Among the most important of his publications, in several of which he had collaboration, are A Field Ornithology (1874); Birds of the North-west (1874); Monographs on North American Rodentia, with J. A. Allen (1877); Birds of the Colorado Valley (1878); A Bibliography of Ornithology (1878–1880, incomplete); New England Bird Life (1881); A Dictionary and Check List of North American Birds (1882); Biogen, A Speculation on the Origin and Motive of Life (1884); The Daemon of Darwin (1884); Can Matter Think? (1886); and Neuro-Myology (1887). He also contributed numerous articles to the Century Dictionary, wrote for various encyclopaedias, and edited the Journals of Lewis and Clark (1893), The Travels of Zebulon M. Pike (1895) and "the personal narrative of Charles Larpenteur", Forty Years a Fur Trader on the Upper Missouri (1833–1872), published in 1898.

[edit] References

Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). "Coues, Elliott". Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). "Coues, Elliott". Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.  This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.

[edit] External links

| Persondata |

| Name |

Coues, Elliott |

| Alternative names |

|

| Short description |

|

| Date of birth |

September 9, 1842 |

| Place of birth |

Portsmouth, New Hampshire |

| Date of death |

December 25, 1899 |

| Place of death |

|